- California Assembly OKs highest minimum wage in nation

- S. Korea unveils first graphic cigarette warnings

- US joins with South Korea, Japan in bid to deter North Korea

- LPGA golfer Chun In-gee finally back in action

- S. Korea won’t be top seed in final World Cup qualification round

- US men’s soccer misses 2nd straight Olympics

- US back on track in qualifying with 4-0 win over Guatemala

- High-intensity workout injuries spawn cottage industry

- CDC expands range of Zika mosquitoes into parts of Northeast

- Who knew? ‘The Walking Dead’ is helping families connect

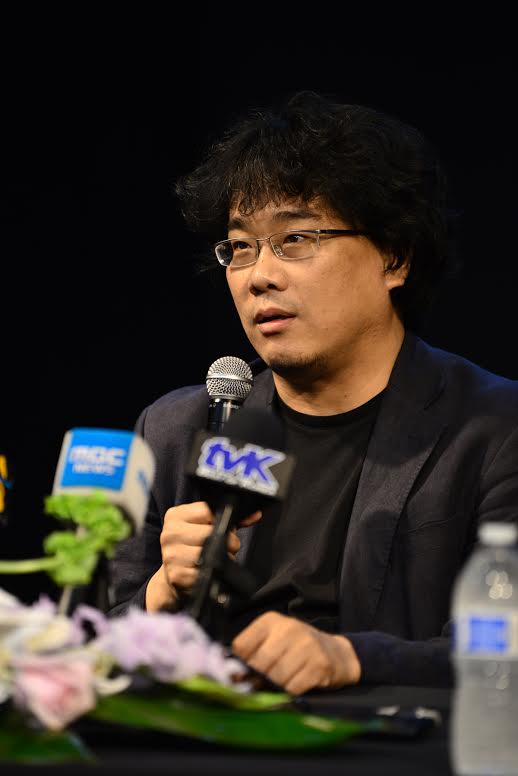

Bong Joon-ho talks about “Snowpiercer” and more in L.A.

Korean filmmaker wants to hear people say, “His best work is his latest work.”

Director Bong Joon-ho inside the Korean Cultural Center Los Angeles for the “Snowpiercer” press conference. (Kim Young-jae / The Korea Times)

By Tae Hong

Director Bong Joon-ho, whose genius as a noted Korean filmmaker has long attracted international moviegoers’ affections, finally saw his snowy apocalyptic film, “Snowpiercer,” make its long-awaited U.S. debut on Wednesday.

Not only was it the first showing of the feature to American audiences, despite the film having been released almost a year ago in Korea, it also had the honor of opening the 20th Los Angeles Film Festival.

Bong, 44, easily accepts that filmmaking is all he does and everything he does.

“I don’t exercise, I don’t fish, I don’t play board games,” he says. “I just watch films or I make films. I have no outlet for stress.”

If “Snowpiercer” was an outlet of sorts, it was an expensive one. The pic broke Korean records for big-budget filmmaking at $39 million.

Equipped with guns and axes and a sushi station and baby-eating tail sectioners, it also left a lot of unanswered questions, most of all this: What does it all mean?

“There’s a lot of layers, but one thought is that humans are poor souls,” Bong says. “The movie is a story about the system, in an abstract sense.”

A bevy of talents, including Chris Evans, John Hurt, Song Kang-ho, Ed Harris, Tilda Swinton, Ko Ah-sung, Octavia Spencer and Jamie Bell, star in the two-hour spectacle about a revolution that arises inside a train that holds humanity’s only survivors.

In the film, Wilford, the idolized head of the train, tries to maintain the system because he believes the train is the world, Bong explains. Then there’s Curtis, the tail end leader, who tries to change the system with a revolution. Finally, Nam-goong Min-su, a druggie securities expert, tries to completely destroy the system and escape from it into the outside world.

“So there’s the maintainer, the changer and the one who just denies the system. We’re all one of these people in real life. They all have a degree of legitimacy,” he says. “The end of the film comes about because of Nam-goong Min-su. Curtis may lead the story, but Nam-goong Min-su determines the end as he blows up the door. He may have sacrificed himself, but the young kids finally escape. That’s the final message I wanted to tell.”

Essentially, filming took place inside actual train-section-sized containers three meters wide and very, very long.

“It both excited and scared me, to film for hours inside a train space,” he says. “I thought this kind of opportunity [to film in a train] would come just once. I wanted to show everyone the ultimate train film. I thought, ‘Other directors will never be able to film another train movie.’ I had those immature thoughts, and at the same time I was scared.”

The disadvantage — each section being the same narrow, confined space no matter how it was decorated — added onto the director’s struggle and experimentation with camera angles and with movement.

Actors in the cast each move differently, he says. The challenge was figuring out how to portray their distinct movements.

Bong speaks during the “Snowpiercer” press conference at the KCCLA. (Kim Young-jae / The Korea Times)

Bong had had some of them specifically in mind while he was co-writing the screenplay with Kelly Masterson, the writer behind “Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead.”

Although the movie is based on a French graphic novel, “Le Transperceneige,” only its basic premise, of humanity’s only survivors living on a train traveling through a desolate, snow-covered world, remains in the film.

Characters like Swinton’s Mason and Evans’ Curtis were Bong’s creations.

Mason was originally a male character before he met Swinton at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival and started imagining her as a fun fit for the shrill, bug-eyed minister, he says.

Song and Ko, both of whom Bong had worked with before in “The Host,” agreed to join the film while it was only an idea, just “a movie about a train.”

“I told them to get on board,” he jokes. “And they said, ‘Ah, all right.’”

But Evans, who had just risen to worldwide fame as the wholesome and handsome Captain America, was nowhere on the director’s radar before he was introduced to the actor through their mutual agency.

“I had no interest in him at first,” he recalls.

The Captain came with a recommendation from an American casting director, who told Bong about his independent films in between the Marvel films. “Puncture,” a 2011 pic in which the actor plays a drug-addicted attorney, clinched the deal for Bong.

Evans, on the other hand, had become interested in “Snowpiercer” in the process of trying to find another movie in which he could break out of his superhero tights.

The actor looked as though he’d already read the scenario even before coming to the first meeting to discuss the movie but pretended as though he hadn’t, Bong laughs. It wasn’t long before Evans signed on.

“The only difficult thing was trying to hide his muscles,” Bong says. “Those Captain America muscles, it wasn’t easy to hide them underneath the costume. He was supposed to be the protagonist of the tail section but had the physique of a bodybuilder.”

Real-life issues inspired elements of his screenplay, he says. In particular, he was struck by human rights reports of child laborers in the South Pacific who are underpaid and used for their small body sizes to gather materials from the ocean for use as ingredients in luxury foods.

In the movie, the young son of a tail section passenger is taken from his mother and forced to work underneath the floors of the front end to keep the engine running after being deemed the right size by measuring tape.

“I drew inspiration from [the reports]. It’s a terrible thing,” he says. “To think that something like that isn’t just in a sci-fi movie but a part of our actual lives is both surprising and painful to think about.”

The film, which has seen its premiere around the world since August 2013, still has openings coming in England, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, he says.

The director, as always, plans to move forward. He’s currently working on two film scenarios — one fully Korean and one partially in English — but has yet to decide which will be his next project.

He expects to know by the end of the year.

“Just as Psy has been able to enjoy his music with Americans and the rest of the world, I’d like [the process] to be natural,” he said during a press conference for the film just before the interview. “It won’t be easy, but I’ll work to hear the review, ‘His best work is his latest work.’”