- California Assembly OKs highest minimum wage in nation

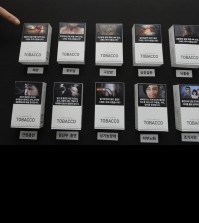

- S. Korea unveils first graphic cigarette warnings

- US joins with South Korea, Japan in bid to deter North Korea

- LPGA golfer Chun In-gee finally back in action

- S. Korea won’t be top seed in final World Cup qualification round

- US men’s soccer misses 2nd straight Olympics

- US back on track in qualifying with 4-0 win over Guatemala

- High-intensity workout injuries spawn cottage industry

- CDC expands range of Zika mosquitoes into parts of Northeast

- Who knew? ‘The Walking Dead’ is helping families connect

Producer Glen Choi is out to shape the future of K-pop

By Tae Hong

Glen Choi was a 14-year-old Korean American kid from Beverly Hills when he entered the K-pop industry in 1996 as one-half of IDOL, a pop duo who breezed their way to the top of South Korean music charts.

Nearly 20 years later, the former singer and first-ever South Korean idol is back on the scene, but in a different role: as a music producer (you can thank him, his team of producers and 2PM vocalist Jun. K for this fall’s hit song “Go Crazy”) and as an informal Korean pop industry adviser.

“It sounds different, and you can just tell off the bat that it’s not Korean-made,” he said about the song, sitting inside a small Los Angeles studio. “You didn’t have to stick to that super-serious, sexy man, cool-guy, K-pop thing.”

Choi, who experienced the yesterday of K-pop and who’s now thrown himself into thinking about the today and tomorrow of it, has an image of the genre he’d eventually like to see.

“I think [K-pop]‘s gotta be a little bit more universal. [Producing] is spotting a trend, seeing where there’s a void in music,” he said. “Coming out with originality, authenticity.”

And it’s what he wants to do as he continues his entrance into the rapidly growing genre.

Choi’s projects so far have taken him to projects with major labels like JYP Entertainment (he knows CEO Park Jin-young from performing with him in the ‘90s and produced the Wonder Girls’ “Dear Boy”), SM Entertainment (f(x)’s “Ending Page,” “Step”) and KeyEast (Kim Hyun-joong’s “Tonight”).

His ideas about K-pop and where it should be headed aren’t based only on his experience working with American artists like Pitbull and Wiz Khalifa or his short stint as a marketing guy at Universal Music post-graduation from Cal Poly — they come from the unique perspective of someone who knows the beginnings of the Korean pop idol movement all too well.

There was no such thing as K-pop when he started, Choi said.

He was 10 when he arrived in Korea, following his mother — a famous film actress from the 1970s by the name of Choi Naomi who returned after living in Los Angeles — to live there.

By 1995, he’d developed a love for DJing, for playing music in front of others. He’d begun receiving vocal and dance training in preparation for debut. Meanwhile, bands like the Backstreet Boys and Spice Girls were rocking boom boxes overseas.

IDOL was an unfamiliar splash on the face of the industry as the two teenagers climbed the charts with “Bow Wow,” eventually hitting No. 1 months before the debut of future K-pop idol legend H.O.T. But with stardom came trouble — thrown straight onto the stage and onto television, young Choi was ill-equipped to handle the newfound fame and stress level that came with his demanding schedule.

“I was the first. There were no teenage kids on stage at the time. … We had to break a lot of grounds and break boundaries,” he said. “It was tough because Korea at the time was old school and very harsh on people that couldn’t speak Korean. Now, everyone wants to learn English. It shows how limited Korea was.”

It’s come a long way since then, and K-pop along with it.

To the producer, who has a grasp of both the Korean and American music industry (“I’ve done every single job in the business,” he said. “I’ve been a manager for an artist, producer, singer, songwriter, choreographer, DJ.”), its current expansion and growing global reach looks like an opportunity like no other.

“Korean music is having a really hard time coming into the U.S.,” he said. “It just doesn’t have the right type of sound. It doesn’t have the right type of authenticity to it.”

The key to appealing to the American market lies with artist participation, he said, not unlike the role played by Jun. K with “Go Crazy.”

“We were able to work with the artist instead of the artist being given a song and being told to perform it,” Choi said. “[K-pop] should be artist-driven music. I can tell when [2PM] performs it, it’s genuine. It’s real. It’s theirs. They made it, they own it.”

It’s the future of K-pop and the element that will lend bands the authenticity to successfully enter the U.S., he said. According to Choi, American producers he interacts with have a wide range of opinions on the genre — the point is, though, that they’ve taken notice of it, he said.

“There’s some people that are excited because [K-pop] is a whole new ground that they’ve never embarked on. It’s musical, it has a big audience. It’s getting bigger,” he said. “On the bottom side, it’s too manufactured. It’s a little cheesy. The sound quality is low. [The opinions] are a broad spectrum.”

Choi said he’s headed toward taking on a role as a mentor to artists and as a liaison between the American and K-pop industries.

“I can see what’s happening in Korea, where the weak points are, how we can develop it into something better,” he said. “It’s to bring higher-quality products to the market.”

Based in Los Angeles, Choi acts as the music director of Artisans Music, a group of producers and songwriters. He’s also a DJ who goes by “dj nure” — meaning “new revolution.”

“I’m always trying to do something new, to bring a revolution,” Choi said. “As a kid, I changed K-pop in a sense. I don’t want to do something that’s already been done.”