- California Assembly OKs highest minimum wage in nation

- S. Korea unveils first graphic cigarette warnings

- US joins with South Korea, Japan in bid to deter North Korea

- LPGA golfer Chun In-gee finally back in action

- S. Korea won’t be top seed in final World Cup qualification round

- US men’s soccer misses 2nd straight Olympics

- US back on track in qualifying with 4-0 win over Guatemala

- High-intensity workout injuries spawn cottage industry

- CDC expands range of Zika mosquitoes into parts of Northeast

- Who knew? ‘The Walking Dead’ is helping families connect

For many others, reunions put on shelf forever

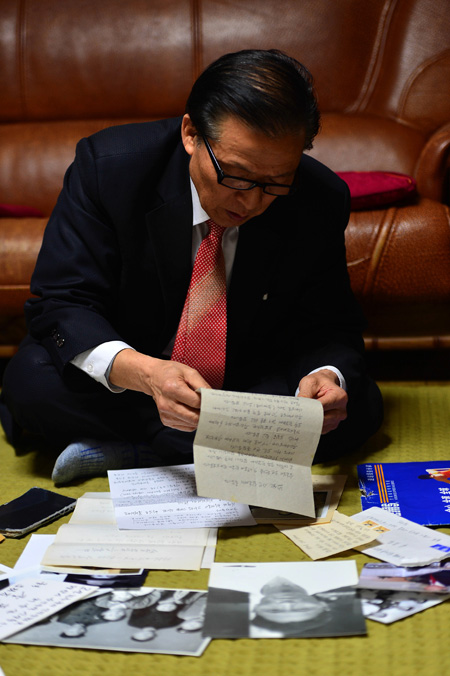

Jang Sa-in, 74, reads a letter from his brother who died in North Korea last year, at his Sadang-dong home in southern Seoul, Thursday. (Korea Times photo by Shim Hyun-chul)

By Yoon Sung-won

While about 200 separated family members from South and North Korea are enjoying their long-overdue reunions at Mount Geumgang, many more here have to look to them with envy.

One of those is Jang Sa-in, a 74-year-old who lives in Sadang-dong, southern Seoul.

Jang pulled out a letter from his older brother from the North. He was told through a source that Sa-guk died last year.

“I never knew that time would pass so fast. Now I turned 80 and I still can vividly describe the scenery in our hometown… I suppose you already entered your 70s. I believe you and your sisters have served mother well so far,“ Jang read haltingly during an interview Thursday.

He explained how it all began.

The Jangs’ story is different from those of most other separated families, who left their loved ones behind when they fled the North.

His brother joined the Armed Forces in June 1949.

When the war broke out in 1950, he went missing in battle. When the truce came three years later, the Jang family received notification that the missing brother was presumed to be killed in action.

So when he was told that his brother was alive in 2008, living with his own family in the North, it shocked him.

“My mother never believed that her son was dead,” he remembered.

“Looking to my mother, I prayed she would give it up,” Jang said.

“Then, the news that my brother was alive made me mortified, regretting what I did,” he said. “I was also happy to think that my mom’s prayer was answered.”

That, however, was in hindsight and the start of a new heartbreak for the Jangs.

With letter and photo in hand, Jang rushed to the Korea National Red Cross (KNRC), asking it to help him have a reunion with his brother.

He was told “not so fast,” and asked to put his name on a very long waiting list.

He was waiting, but his turn didn’t come because frosty inter-Korean relations put reunions on hold.

Last year, he came to know that his brother died in North Korea in September.

Jang was lost in grief.

His wife Lee Myeong-soon, who sat with her husband, intervened.

“At first, he couldn’t accept that his brother really passed away and became ill for a while,” she said. “He even went to China to meet his liaison to the North twice and there he finally confirmed that his brother had died.”

Although he continues to try and accept his brother’s death, Jang has another hope and mission — fulfilling his brother’s will to take care of his surviving family.

“I don’t want to blame the Unification Ministry or the KNRC. But most of us understand that time is running out for us,” Jang said. “I expect authorities to make an extra effort to broaden the opportunity for reunions for people like me.”

Among the applicants, over 57,000 have already passed away and more than half are aged over 80. About 70,000 separated family members live in the South.

“Though more than six decades have passed, the pain of separation is still fresh to my family,” Jang added. “Though it is people like me who bear the pain, I hope more people, young or old, understand it as we all live in this divided history.”