- California Assembly OKs highest minimum wage in nation

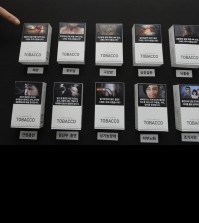

- S. Korea unveils first graphic cigarette warnings

- US joins with South Korea, Japan in bid to deter North Korea

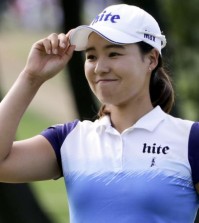

- LPGA golfer Chun In-gee finally back in action

- S. Korea won’t be top seed in final World Cup qualification round

- US men’s soccer misses 2nd straight Olympics

- US back on track in qualifying with 4-0 win over Guatemala

- High-intensity workout injuries spawn cottage industry

- CDC expands range of Zika mosquitoes into parts of Northeast

- Who knew? ‘The Walking Dead’ is helping families connect

S. Koreans sue government over salt farm slavery

A man walks through a salt farm on Sinui Island, south of Seoul, South Korea. Life as a salt-farm slave was so bad Kim Jong-seok sometimes fantasized about killing the owner who beat him daily. Freedom, he says, has been worse. In the year since police emancipated the severely mentally disabled man from the farm where he had worked for eight years, Kim has lived in a grim homeless shelter, preyed upon and robbed by other residents. He has no friends, no job training prospects or counseling, and feels confined and deeply bored. (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)

SEOUL, South Korea (AP) — Eight men who had been held as slaves at South Korean salt farms for several years took the government to court on Friday for alleged negligence and police inaction they say largely caused and prolonged their ordeal.

In the lawsuit filed at the Seoul Central District Court, lawyers sought a compensation of 30 million won ($25,860) for each of the men from the central government and two island counties, where the farms were located. The plaintiffs have different levels of disabilities, and were enslaved at the rural islands off South Korea’s southwest coast for as many as 20 years.

More than 60 slaves, most of them mentally ill, were rescued from the islands following an investigation led by mainland police early last year. The slavery was revealed weeks earlier when two police officers from Seoul came to Sinui Island and rescued one of the slaves who had been reported by his family as missing.

Dozens of farm owners and job brokers were indicted, but no regional police or officials were punished despite multiple interviews in which the victims said some knew about the slaves and even stopped escape attempts.

The disturbing cases of abuse, captivity and human trafficking were highlighted in a months-long investigation by The Associated Press published earlier this year, which showed that slavery has long thrived in the islands and will likely continue to do so without stronger government attempts to stem it.

Choi Jung-kyu, one of several lawyers behind the lawsuit, said he was expecting an uphill battle in court as compensation suits against the government in human rights abuse cases are rarely successful in South Korea. This is mainly because, he said, the South Korean law puts the burden of proof entirely on the plaintiffs in non-criminal cases.

“It’s difficult because we are mainly relying on what our plaintiffs told us, while the defendant, which is the government, holds all the information to prove it and can’t be forced to give them up,” Choi said.

Regardless of the outcome, the lawsuit is meaningful because it would raise awareness and put pressure on the government to do more to protect vulnerable people from human trafficking and slavery, he said.

Seoul’s Justice Ministry, whose minister will legally represent the central government in the case, had no immediate comment.

The rescued slaves were mostly disabled and desperate people from mainland cities who were lured to the islands by “man hunters” and job brokers hired by salt farm owners, who would beat them into long hours of backbreaking labor and confine them at their houses for years while providing little or no pay.

Choi said there were strong reasons to believe that local police officers and administrative officials were closely connected with salt farm owners and villagers and helped them keep the victims enslaved.

One of the plaintiffs told the lawyers that he ran several times to a police station at Sinui Island for help, but the officers returned him to his owner each time. Another man said he managed to escape and find his way to the island’s port, but workers there refused to sell him a ticket until his owner came and took him back.

Local officials failed to regularly monitor the work and living conditions at the salt farms, and some job brokers who helped lure the victims are still in business in the nearby mainland port of Mokpo, Choi said.

Slavery has been so pervasive that regional judges have shown leniency toward several perpetrators. In suspending the prison sentences of two farmers, a court said that “such criminal activities were tolerated as common practice by a large number of salt farms nearby.”

The plaintiffs in the lawsuit against the government include Kim Seong-baek, the first slave rescued from the islands by Seoul police officers.

One of the officers, Seo Je-gong, now retired, told AP he felt the need to run a clandestine rescue operation without telling local officials because of concerns about collaboration between the island’s police and salt farm owners. Carrying fishing rods, Seo and his partner disguised themselves as tourists before finding Kim and bringing him back to Seoul. Kim’s former slave owner was unsuccessful in appealing his 3 ½-year prison term earlier this year.