- California Assembly OKs highest minimum wage in nation

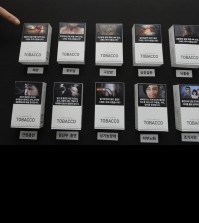

- S. Korea unveils first graphic cigarette warnings

- US joins with South Korea, Japan in bid to deter North Korea

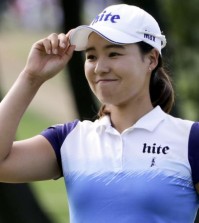

- LPGA golfer Chun In-gee finally back in action

- S. Korea won’t be top seed in final World Cup qualification round

- US men’s soccer misses 2nd straight Olympics

- US back on track in qualifying with 4-0 win over Guatemala

- High-intensity workout injuries spawn cottage industry

- CDC expands range of Zika mosquitoes into parts of Northeast

- Who knew? ‘The Walking Dead’ is helping families connect

How far will S. Koreans go to get into top universities?

BUSAN, South Korea (AP) — A documentary film about the social and personal costs of South Koreans’ craze for being admitted to the nation’s top three universities depicts a system that is a far cry from President Barack Obama’s praise of the Asian country as a model for U.S. educational reforms.

“Reach for the SKY” follows three students and a teacher working for a test-prep company before and after South Korea’s college entrance exam.

The once-a-year exam is the final and the crucial checkpoint to enter “SKY,” a shorthand reference to the country’s three most prestigious universities.

Gaining admission to a SKY school is the ultimate goal of one’s 12-year education and is akin to being admitted to a better class of people who later lead a company or the country. Only the top few test-takers reach the SKY. The rest spend another year or two working to improve scores and retake the test – the “repeaters” in the movie – or they are doomed to live out their lives as losers.

“We wanted to focus on the kids who are in a race for their own life,” said South Korean co-director Choi Wooyoung. “And think about the energy that we all consume only for the top 1 percent.”

The documentary, a co-production of Belgium and South Korea, premiered during the 20th Busan International Film Festival, which ended Saturday.

The scenes in the film cannot be farther from Obama’s image of South Korea as a country where schoolteachers are revered as “nation builders” and students stay longer at schools for the better.

The test-prep English teacher is seen on film as a guru, a rock star of test prepping, who reads an English sentence, “Have the courage to follow your heart and intuition,” to students who do not.

He’s drives a BMW in an early scene and later is shown backstage being introduced as if he were the world’s boxing champion. As he steps onto the stage, applause from tens of thousands of students fills the Olympic stadium. As the test-prep employee shares strategies for the upcoming exam, the camera pans the stadium and it becomes clear who the real teacher is in the country. The students are riveted as if they were watching Apple announce a new iPhone.

For the foreign director of the documentary, the stadium scene was one of the astounding aspects of the South Korean educational system.

“But none of it is ridiculous, if you understand the context. And somehow I hope that’s what this film can show,” said co-director Steven Dhoedt.

Choi and Dhoedt got rare scenes of life at a private boarding school for “repeaters,” recent high-school graduates dedicating one or more years at a testing boot camp to try to attain SKY-level scores when they retake the exam. The place embodied the academic craze in the Korean education system, Dhoedt said, and getting access there meant easing worries that the crew’s presence would distract the students from preparing for the college exam.

“It really sums up the level of commitment that students and parents are willing to put in to get to a good university,” the Belgian director said.

The climax of the movie comes on the day of the Suneung exam, which dictates every corner of life in South Korea, not just those of the three students the directors follow. The landing of an airplane is controlled so that the noise will not interfere with the listening test, and a news anchor describes the exam’s progress in a live broadcast outside a full-day Suneung testing venue.

The documentary will likely add a new dimension to the global discussion about South Korean education, which has been thus far spotlighted often for its ability to produce academically excellent, hard-working students or for its creativity-stifling, hyper-competitive environment with one of the world’s fastest-growing youth suicide rates.

“The most important discovery I have made is that a lot of students are often victims of their own ambition and aspirations,” Dhoedt said. “Before I thought, rather naively, that they were all victims of a very demanding school system of which there was no escape. But it’s not necessarily that black and white.”

Minjun, one of the “repeaters” in the movie, decides to spend another year to improve his scores even though his father, a self-made man, says going to a good university is not all that important to have a good life.

“But the boy doesn’t want to believe him. He has told himself he needs to get into Korea university, at all cost. Because he feels that’s what society has told him to do his entire life,” said Dhoedt.

The film took four years to complete, since beginning researching in the winter of 2011 and filmed throughout three Suneung exams.

“Reach for the SKY” is scheduled to be aired on the National Geographic channel in South Korea and other television networks in Belgium, Germany and Finland.

Pingback: Seoul Or Busan Teach English | join - best language schools

Pingback: South Korea Teach English University | exercises - online teachers

Pingback: Seoul Or Busan Teach English | thai - language teachers

Pingback: Epic South Korea Teach English | Becoming Multilingual