- California Assembly OKs highest minimum wage in nation

- S. Korea unveils first graphic cigarette warnings

- US joins with South Korea, Japan in bid to deter North Korea

- LPGA golfer Chun In-gee finally back in action

- S. Korea won’t be top seed in final World Cup qualification round

- US men’s soccer misses 2nd straight Olympics

- US back on track in qualifying with 4-0 win over Guatemala

- High-intensity workout injuries spawn cottage industry

- CDC expands range of Zika mosquitoes into parts of Northeast

- Who knew? ‘The Walking Dead’ is helping families connect

There is no Korean wave

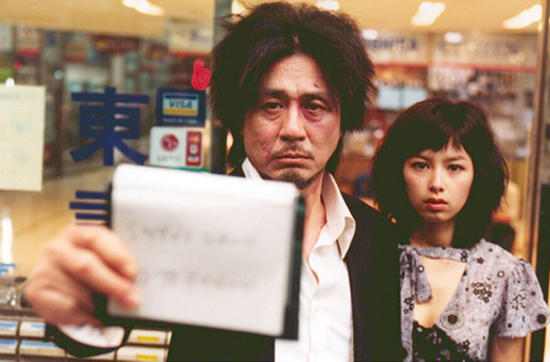

Choi Min-sik,left, and Kang Hye-jung star in the movie “Old Boy” by director Park Chan-wook. The film won the Grand Prix Prize in 2004 at the Cannes Film Festival. (Korea Times file)

By Michael Hurt

In recent years, Korean pundits and other interested parties have tried to explain the phenomenon of the so-called “Korean wave.”

However, in my time as a member of the Presidential Council on Nation Branding under the Lee Myung-bak administration, along with my years of producing content about Korean culture through blogs, podcasts, and photography, I have come to realize that the worst people whom you can ask to explain Korean culture to the outside world are actually Koreans.

Hindered by nationalist blinders, and often more interested in or fascinated by the idea that any non-Koreans are “recognizing” Korean culture or even giving a nod in the direction of the Korean Peninsula, some boosters of the idea that there is a “Korean wave” have given a name to a phenomenon that is easily explainable in terms of Korean national development and structural changes in Korean society. Indeed, now there are large government and private monied interests that are very caught up in the project of defining, packaging, exporting, and otherwise selling aspects of Korean culture. But few realize that there is actually no “wave” to speak of at all, not to mention the fact that the metaphor itself is pretty faulty, since even if there were a discernible Korean “wave,” one must remember that every so-called “wave” — to extend the metaphor — must inevitably ebb, recede, and give way to other waves that will continue to come and go in time.

In the beginning of the classic Hollywood film “The Matrix,” a young sage says to Neo:

“Do not try and bend the spoon — that’s impossible. Instead, only try to realize the truth…There is no spoon…..Then you will see that it is not the spoon that bends, it is only yourself.”

In a similar way, I’m declaring that the so-called “Korean wave,” as I have asserted above, simply doesn’t exist.

Now, before you grab your torches and pitchforks, allow me to explain what I mean here. What many people referred to as the “Korean wave” is nothing more than the construction of a South Korean media, and diaspora members who see a pattern that doesn’t really exist to anyone outside of Koreans’ desire for recognition and have simply decided to give it a name. In the beginning of what many people now call the “Korean wave,” there was simply a movie that had managed to garner direct praise from jurors at the Cannes film Festival — “Old Boy.”

I’ll use this as an example with which to explain what I’m talking about. In order to understand the phenomenon of what Koreans call “cultural exports” and the so-called “culture industries,” one has to see things in the larger picture and without the distorting lens of ethnic nationalism. To be completely frank about the history of Korean films, it is safe to say that until the late 1990s, there weren’t that many Korean films worth anyone’s interest who wasn’t already intimately involved with Korea or Korean culture, at least in terms of the international film standards against which many films across the world are measured and given or denied the recognition of awards. This being said, it is instructive to talk about why this was the case, since I am not trying to assert that there weren’t many internationally worthy films of Korean origin simply by sake of the fact that they were Korean. There are other factors here, most of which are related to the level of overall national development as well as of the domestic film industry itself.

When thinking about how the initial so-called “Korean wave” began in film, it is important to remember that it was conditions and circumstances within the country itself that hobbled Korean Cinema prior to Old Boy.

When heavy and direct government censorship was relaxed in the late 1990s, many films were able to be made that previously would not have been possible. Once the heavy hand of the government censor had come off the neck of most Korean film directors, there was a sudden flowering of extremely creative and interesting films.

“Old Boy” was one of them, and was representative of a particular Korean cinematic aesthetic that French film jurors connected with and rewarded with prizes and recognition.

Suddenly, the meme was out — Korean films tended to have a certain sensibility that Western audiences were connecting with. Moreover, the film itself displayed the extremely high production values that had become de rigueur in mainstream Korean Cinema by the late 1990s.

Put simply, the Korean film industry had matured, and the shackles put on that industry by the Korean government had been loosened. This allowed the production of individual good works that eventually found recognition at international film festivals.

Looked at from another perspective, the Korean desire for any form of recognition from white Western countries is so strong that the recognition of a singular Korean cultural product is cause for joy and celebration, while recognition of two such products is an achievement so astounding that the pattern or phenomenon must be given the name, such as a “wave” or other such evidence that Korean culture is “ascending” or “on the rise” or somehow otherwise indicative of careers generally “superior” culture. The recognition of more than two Korean cultural products has been described as “Korean culture taking over the world” or receiving what many Korean nationalists absolutely crave: the Holy Grail of “recognition.”

However, I see the increased presence of Korean cultural products on the international scene as a good and natural result of the loosening of structural restrictions on the artistic sectors of civil society. Generally speaking, there isn’t a recognition of Korean cultural products to the extent that Koreans hope or even believe that there is, but rather a natural increase in the number of high-quality Korean cultural products that make it onto the international scene by virtue of the fact that there are simply many more high-quality cultural products being produced in general. It’s only natural and inevitable that more of them will be recognized on an international level.But that doesn’t a “wave” make.

Don

November 6, 2013 at 7:33 PM

I lost interest by the end of the third paragraph. No offense, but you need to get to the point a little quicker.

Greg

November 6, 2013 at 8:23 PM

What is he talking about? Who is he arguing with except himself?

Greg

November 6, 2013 at 8:25 PM

Maybe he should’ve started with reading the wikipedia page.

“The Korean Wave[2] (Hangul: 한류; Hanja: 韓流; RR: Hallyu[1]; MR: Hallyu) is a neologism referring to the increase in the popularity of South Korean culture since the late 1990s. The term was originally coined in mid-1999 by Beijing journalists who were surprised by China’s growing appetite for South Korean cultural exports. They subsequently referred to this new phenomenon as “Hánliú” (韓流), which literally means “flow of Korea”.[3][4]“

Jam

November 6, 2013 at 9:07 PM

I enjoyed the article. Thought it was insightful.

andrew

April 1, 2014 at 8:01 AM

a korean music video has 2 billion views;

the most watched music video on the planet, of all times, is a korean video.

enough said.