- California Assembly OKs highest minimum wage in nation

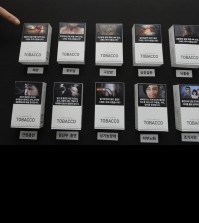

- S. Korea unveils first graphic cigarette warnings

- US joins with South Korea, Japan in bid to deter North Korea

- LPGA golfer Chun In-gee finally back in action

- S. Korea won’t be top seed in final World Cup qualification round

- US men’s soccer misses 2nd straight Olympics

- US back on track in qualifying with 4-0 win over Guatemala

- High-intensity workout injuries spawn cottage industry

- CDC expands range of Zika mosquitoes into parts of Northeast

- Who knew? ‘The Walking Dead’ is helping families connect

N. Korea is slowly, but surely adopting capitalism

In this Tuesday, May 5, 2015, photo, a man sits in front of portraits of the late North Korean leaders Kim Il Sung, left, and Kim Jong Il, right, as he uses his smartphone in Pyongyang, North Korea. North Korean officials have unveiled a mobile-friendly online shopping site. (AP Photo/Wong Maye-E)

By Kim Hyo-jin

North Korea is changing, at least in terms of what people wear and consume.

In terms of political rhetoric and military activity, the isolated country is still a repressive Stalinist state, but its economy is becoming increasingly capitalist.

As the state rationing system has weakened since the famine of the 1990s, people have mainly turned to trading on markets and person-to-person trade to survive.

The very basics of survival in fact ― food, clothes and shelter ― can now all be privately bought and sold for profit.

It’s not just among civilians that this phenomenon is occurring. Even the government has set up online shops for food and clothes — although a very limited number of the North Korean population can actually access them.

With this new economic activity, comes new demands.

Private financing and even insurance policies have become available in recent years to moneyed North Koreans, many of whom are fond of saying, “You can buy anything except a cat’s horn” in these markets, meaning if it exists, you can probably buy it.

‘Jangmadang’ Generation

“People call those who do not know how to do business an idiot,” Kim Sang-un, 32, a North Korean defector who left North Korea in 2009, told The Korea Times. ”Money equals power, that’s the norm planted in our generation’s minds.”

Kim is part of what experts are calling the ‘jangmadang’ generation young North Koreans who grew up within a market economy, and are at the forefront of the associated social and economic changes. The word, jangmadang, is a North Korean word which literally means ‘marketplace’.

The ‘Jangmadang’ generation refers to young adults aged from 18-35 who grew up during and after the famine of the 1990s. It was the famine that caused decentralization of the economy and led to people trading on markets.

Those in their 20s and 30s learned to engage in business activities to survive from an early age and such experiences opened up their eyes to capitalism.

Kim said he too used to engage in market business as a cigarette wholesaler in his hometown of Dancheon, South Hamheung Province.

“I also believed that being loyal to the party doesn’t bring you food, but business does,” he said, citing trials in business as a natural and common thing among his cohorts.

The generation consists of 25 percent of the total population, according to Sokeel Park, head of research at the U.S.-based non-profit group Liberty in North Korea (LiNK).

He said they will add momentum for change within North Korean society in a decade or two.

“They are native capitalists, and because of access to foreign media they are also more cosmopolitan and less socially conservative than the official North Korean ideal, that their parents generation aligned more closely with,” he said.

“This presents a long term challenge to the Pyongyang government.”

An Chan-il, the head of the World North Korea Research Center, agrees.

“The impact brought by the young generation has already loosened the state’s grip on society,” he said. “The time will come soon for the regime to decide to open up the society in the face of rising demand from the Jangmadang generation.”

Young North Korean women wearing high heels and holding designer bags in Pyongyang. The photo, published in “Dazed & Confused” was taken by freelancer Lu-Hai Liang, who visited the North this year. (Yonhap)

Fashion and Trends

But it’s not just food and basics that people now buy from these ‘jangmadang’ traders. Where there is money, there is a market for new things and nowhere is this more apparent than with fashion, even in North Korea.

British fashion magazine Dazed & Confused posted pictures in August, showing North Korean women holding fake designer bags such as Dior and Prada.

Women wearing high heels and carrying brand bags are not an unusual scene on the streets, according to visitors to North Korea.

“Designer products are very popular in North Korea, especially in Pyongyang,” said Troy Collings of Young Pioneers Tours, a travel agency that specializes in tours to the isolated country.

“Most people settle for Chinese counterfeits but still follow trends as closely as they can.

“Surprisingly, many people in Pyongyang I know can quickly tell the difference between legitimate designer goods and fakes,” he said.

Collings, who has frequently visited the country over several years, says that people are getting more adventurous with fashion. It is not an exception for guys either.

“Lately, I’ve seen a lot of young men in Pyongyang with haircuts that wouldn’t look so out of place in Taiwan or dare I say, Seoul,” he said.

Dyeing their hair brown is common among girls and they get away from the authorities by claiming it is their own hair, write North Korea watchers Daniel Tudor and James Pearson in their recently-published book, ‘North Korea Confidential: Private Markets, Fashion Trends, Prison Camps, Dissenters and Defectors.’

They noted that the fashion trends are driven by young people who have been exposed to foreign films or TV shows on DVDs or on files stored on USB sticks. They are keen on mimicking celebrities.

For instance, the book states that fake versions of a pair of shoes worn by South Korean actress Kim Tae-hee went on sale in a Pyongyang department store for US $120.

Growing Insurance Industry

As more North Koreans earn money in the unofficial economy, the isolated country’s insurance sector is also growing, with everything from mobile phones to cars now eligible for financial protection.

The Korea National Insurance Corporation (KNIC), the state insurance company, stated on its website in mid-August that there was an increase in the number of North Korean insurable consumer goods and commodities.

The country’s fastest growing target market for insurance appears to be for mobile phones, with consumer demand ballooning in recent years.

“A majority of Pyongyang people between 20 and 50 years of age have mobile phones,” Tudor and Pearson write in their book.

For North Korean traders, owning a mobile phone is not merely a status symbol, it is a “necessary business expense,” they write.

Koryolink, Pyongyang’s largest and most widely-used mobile service provider now has 2.5 million subscribers, as of June in 2015.

But it is not just mobile phones. Cars can also now be insured.

A car insurance document provided to The Korea Times showed a private car driven by a non-North Korean in the Rajin-Sonbong Special Economic Zone (SEZ) insured by another state-run insurance company for an unspecified amount.

The document, although like many things in North Korea printed on cheap, thin paper, is marked with the official red ink stamp of a state-owned insurance company.

It is still not clear if this insurance policy applies to all private car ownership in the reclusive country. But if so, it could be one of the first times that domestic consumer goods have been insured by a state-owned financial enterprise, experts say.

The new policy could even extend to produce such as fruit and vegetables too _a welcome break for farmers in a country prone to natural disasters.

On its website, the KNIC says it intends to bring to the market a new insurance product covering losses on fruit farms caused by drought, flooding, or landslides.

Experts on North Korea say the growth of industries protecting the financial interests of individuals represents citizens welcoming and embracing the black economy, and movement away from the traditional state-centric grasp on money.

“They are moving towards a market economy,” said Andrei Lankov, a professor at Kookmin University.

“In a sense, they are a market economy now, albeit of a very peculiar type and with a great deal of state intervention.

“Of course, the growing income inequality means that there are rich people who can afford expensive gadgets who also want protection for their property,” he added.

Pingback: Latest Cat Shoes Sale News

Pingback: S. Korea's online shopping hits record high after MERS outbreak