- California Assembly OKs highest minimum wage in nation

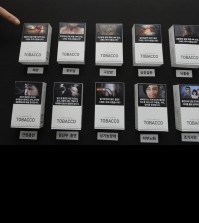

- S. Korea unveils first graphic cigarette warnings

- US joins with South Korea, Japan in bid to deter North Korea

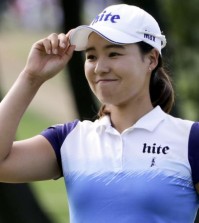

- LPGA golfer Chun In-gee finally back in action

- S. Korea won’t be top seed in final World Cup qualification round

- US men’s soccer misses 2nd straight Olympics

- US back on track in qualifying with 4-0 win over Guatemala

- High-intensity workout injuries spawn cottage industry

- CDC expands range of Zika mosquitoes into parts of Northeast

- Who knew? ‘The Walking Dead’ is helping families connect

3D printing discovery yields curved, flexible circuits

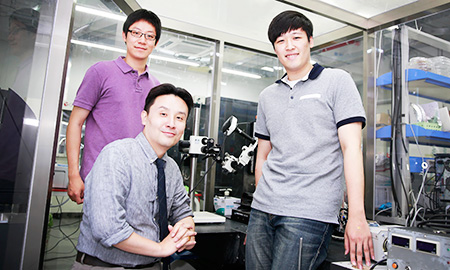

Material Science and Engineering Professor Park Jang-ung, center, poses with his research team at his laboratory in Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology (UNIST) in Ulsan, southeast of Seoul, Tuesday. The institute said Park’s research team has developed an improved three-dimensional printing technology.

(Courtesy of UNIST)

By Yoon Sung-won

A group of Korean scientists have developed three-dimensional (3D) printing technology that can produce curved and flexible electronics circuits on a nanoscale.

Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology (UNIST) said Tuesday the materials science and engineering research team led by Professor Park Jang-ung has succeeded in imprinting 0.001 millimeter ultrafine patterns on plastic circuit boards at room temperature.

The new technology could be used to produce flexible wearable electronics devices.

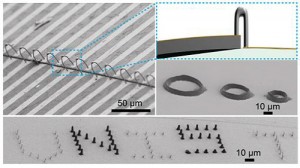

These photos provided by Park and his research team illustrate the product of 3D printing curved and flexible circuits on a nanoscale. (Courtesy of UNIST)

Park said the electronics industry will be able to produce 3D electronic circuits with more diverse designs, which has been difficult with existing photolithographic technology.

“The existing ultrafine pattern production methods in semiconductor manufacturing procedure had difficulties in reproducing 3D patterns. But the new technology can realize it in high resolution,” the professor said.

“We believe the technology has set a new paradigm for research using 3D printing and wearable electronic devices.”

3D printing technology has drawn attention in the electronics industry, but its application to produce electronic circuits has been slow because existing 3D printers could only produce low-resolution results.

Consequently, they have been unable to imprint ultrafine patterns thinner than 0.01 mm. It has also proven impossible to imprint on metallic or plastic materials because printing procedures were done at a high temperature.

The new technology, dubbed “3D electrohydrodynamic inkjet printing,” can produce ultrafine patterns as thin as 0.001 mm, improving the maximum printing resolution 50 times more than before. This is thinner than a red blood cell, Park said.

The new 3D printing technology also lowered the printing temperature as it works at room temperature. This means that textile, fiber, plastic and even more exquisite materials that can be attached to human skin have become possible in 3D printing, the research team said.

The research achievements of Park’s team were published in the German science and technology journal “Advanced Materials” online, Tuesday.

Pingback: South Korean researchers develop a new high-res 3D printer that can print objects thinner than … | 3D Printers Cheap – Incorporating My Skin Care Shop

Pingback: South Korean researchers develop a new high-res 3D printer that can print objects thinner than … | 3D Printing

Pingback: South Korean researchers develop a new high-res 3D printer that can print objects thinner than … | 3D Printing bazar

blood thinner for

February 23, 2016 at 4:55 PM

Cayenne Garlic Ginger Turmeric