- California Assembly OKs highest minimum wage in nation

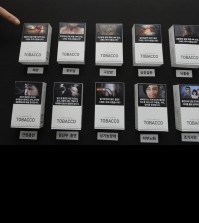

- S. Korea unveils first graphic cigarette warnings

- US joins with South Korea, Japan in bid to deter North Korea

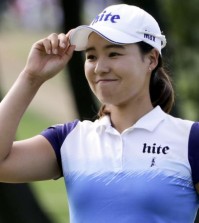

- LPGA golfer Chun In-gee finally back in action

- S. Korea won’t be top seed in final World Cup qualification round

- US men’s soccer misses 2nd straight Olympics

- US back on track in qualifying with 4-0 win over Guatemala

- High-intensity workout injuries spawn cottage industry

- CDC expands range of Zika mosquitoes into parts of Northeast

- Who knew? ‘The Walking Dead’ is helping families connect

[The New Yorker] The two Asian Americas

Pedestrians walk along Grant Avenue in San Francisco’s Chinatown. The neighborhood is the birthplace of Chinese America, and to some extent, the broader Asian America that descended from immigration over the Pacific Ocean throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. (AP Photo/Eric Risberg)

In 1928, an Indian immigrant named Vaishno Das Bagai rented a room in San Jose, turned on the gas, and ended his life. He was thirty-seven. He had come to San Francisco thirteen years earlier with his wife and two children, “dreaming and hoping to make this land my own.” A dapper man, he learned English, wore three-piece suits, became a naturalized citizen, and opened a general store and import business on Fillmore Street, in San Francisco. But when Bagai tried to move his family into a home in Berkeley, the neighbors locked up the house, and the Bagais had to turn their luggage trucks back. Then, in 1923, Bagai found himself snared by anti-Asian laws: the Supreme Court ruled that South Asians, because they were not white, could not become naturalized citizens of the United States. Bagai was stripped of his status. Under the California Alien Land Law, of 1913—a piece of racist legislation designed to deter Asians from encroaching on white businesses and farms—losing that status also meant losing his property and his business. The next blow came when he tried to visit India. The United States government advised him to apply for a British passport.

According to Erika Lee’s “The Making of Asian America,” published to coincide with the fiftieth anniversary of the Immigration and Nationality Act, signed into law on October 3, 1965, this swarm of circumstances undid Bagai. In the room in San Jose, he left a suicide note addressed, in an act of protest, to the San Francisco Examiner. The paper published it under the headline “Here’s Letter to the World from Suicide.” “What have I made of myself and my children?” Bagai wrote. “We cannot exercise our rights. Humility and insults, who is responsible for all this? Me and the American government. Obstacles this way, blockades that way, and bridges burnt behind.”

![일본 사도광산 [서경덕 교수 제공. 재판매 및 DB 금지]](http://www.koreatimesus.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/PYH2024072610800050400_P4-copy-120x134.jpg)