- California Assembly OKs highest minimum wage in nation

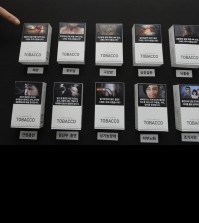

- S. Korea unveils first graphic cigarette warnings

- US joins with South Korea, Japan in bid to deter North Korea

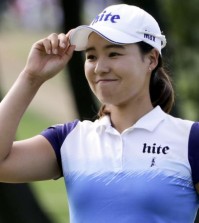

- LPGA golfer Chun In-gee finally back in action

- S. Korea won’t be top seed in final World Cup qualification round

- US men’s soccer misses 2nd straight Olympics

- US back on track in qualifying with 4-0 win over Guatemala

- High-intensity workout injuries spawn cottage industry

- CDC expands range of Zika mosquitoes into parts of Northeast

- Who knew? ‘The Walking Dead’ is helping families connect

Experts divided over assessment of Seoul-Tokyo deal on sex slavery

Former South Korean sex slaves, who were forced to serve for the Japanese Army during World War II, wait for results of a meeting of South Korean and Japanese foreign ministers at the Nanumui Jip, The House of Sharing, in Gwangju, South Korea, Monday, Dec. 28, 2015. The foreign ministers said Monday they had reached a deal meant to resolve a decades-long impasse over Korean women forced into Japanese military-run brothels during World War II, a potentially dramatic breakthrough between the Northeast Asian neighbors and rivals. (Hong Ji-won/Yonhap via AP)

SEOUL (Yonhap) — South Korean experts showed mixed reactions Monday to an agreement by Seoul and Tokyo to resolve the issue of Japan’s wartime sex slavery, saying that improvement of their frayed ties hinges on how to carry out the deal.

Earlier in the day, South Korea and Japan reached a landmark deal to settle the issue of Tokyo’s wartime sexual enslavement of Korean women for Japanese soldiers during World War II.

Under the agreement, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe expressed an “apology and repentance from the heart” to Korean victims of Japan’s atrocities and a 1 billion yen (US$8.29 million) fund, chipped in by the Japanese government, will be set up.

Some experts here welcomed the deal as Japan publicly offered an apology for the victims, one of the main diplomatic tensions between Seoul and Tokyo. But others claimed that the agreement did not specify Japan’s legal responsibility for the issue, leaving a seed of discord over an interpretation of the deal.

“The deal seemed to come out as President Park Geun-hye and Abe made political decisions before this year, the 50th anniversary of normalization of the two countries’ diplomatic ties, comes to an end,” former South Korean Foreign Minister Yu Myung-hwan said.

South Korea has demanded Japan acknowledge state responsibility for the issue and offer proper compensation, while Tokyo insists the matter was settled under a 1965 treaty that normalized bilateral ties.

There are only 46 surviving South Korean victims, raising urgency for the issue to be resolved.

Abe, a conservative politician, had not apologized for Japan’s sexual slavery since taking office in late 2012. He stopped short of making an apology over the issue when he issued a statement in August to mark the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II.

“The deal is deemed as significant progress over the matter, given that Abe has denied Japan’s 1993 landmark apology over the issue,” said Lee Won-deog, a director at the Institute of Japanese Studies at Kookmin University, referring to the Kono Statement.

They said that it is positive that Japan expressed its acute responsibility for the issue and apologized for its wrongdoings, which could serve as a major step forward the future-oriented relations.

“The government should make efforts to listen to the voices of the victims as much as possible when implementing the deal,” said Jo Yang-hyeon, a professor at the Institute of Foreign Affairs and National Security.

But other experts said that the agreement stopped short of specifying Japan’s legal responsibility for the issue. In addition, some of the South Korean former sex slaves immediately denounced the deal, calling it a political collusion between the two countries.

Lee Yong-soo, an 88-year-old former sex slave, voiced strong dissatisfaction with the deal, saying she would ignore the results of the agreement.

“The deal is seen as problematic as it is not legally binding for the implementation aspect,” Lee Na-young, a sociology professor at Chung-Ang University. “It is questionable how much the Korean government has reflected the opinions of the victims.”

![일본 사도광산 [서경덕 교수 제공. 재판매 및 DB 금지]](http://www.koreatimesus.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/PYH2024072610800050400_P4-copy-120x134.jpg)