- California Assembly OKs highest minimum wage in nation

- S. Korea unveils first graphic cigarette warnings

- US joins with South Korea, Japan in bid to deter North Korea

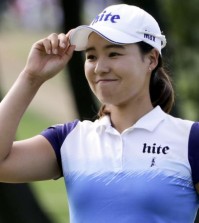

- LPGA golfer Chun In-gee finally back in action

- S. Korea won’t be top seed in final World Cup qualification round

- US men’s soccer misses 2nd straight Olympics

- US back on track in qualifying with 4-0 win over Guatemala

- High-intensity workout injuries spawn cottage industry

- CDC expands range of Zika mosquitoes into parts of Northeast

- Who knew? ‘The Walking Dead’ is helping families connect

Cracking down on Pyongyang is difficult. Here’s why

North Koreans watch a news broadcast on a video screen outside Pyongyang Railway Station in Pyongyang, North Korea, Wednesday, Jan. 6, 2016. Pyongyang has long claimed it has the right to develop nuclear weapons to defend itself against the U.S., an established nuclear power with whom it has been in a state of war for more than 65 years. But to build a credible nuclear threat, the North must explode new nuclear devices — including miniaturized ones — so its scientists can improve their designs and technology. (AP Photo/Kim Kwang Hyon)

SEOUL, South Korea (AP) — Repeatedly over the past six weeks, since the January morning that North Korea surprised the world with its fourth nuclear test, the United States, South Korea, Japan and their allies have vowed to get tough on Pyongyang.

“Reckless and dangerous,” U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry said of North Korean leader Kim Jong Un’s actions. In Japan, the military was put on alert when Pyongyang vowed to follow the nuclear test with a rocket launch — which it did a month later. In Seoul, the government said it would ensure North Korea faces “strong and effective” U.N. sanctions.

But what have North Korea’s critics actually done? Not very much so far, it turns out, and even less that has been strong and effective.

SANCTIONS

Much of the talk about North Korean sanctions comes from Seoul and Washington, but it’s Beijing that holds most of the cards.

Late last week, after the Jan. 6 nuclear test and the Feb. 7 rocket launch, Congress tightened a series of existing sanctions, seeking to deny North Korea money for its weapons programs. The U.S. president already has sweeping powers to impose sanctions on companies and banks that do illicit business with North Korea, which is prohibited by the United Nations from nuclear and ballistic missile tests. The new legislation, which requires President Barack Obama’s signature, takes it up a notch by making it mandatory to blacklist entities engaged with Pyongyang in the nuclear and missile technology trade.

Sanctions on North Korea have been around for years — imposed both by individual countries and the U.N. — but Pyongyang’s weapons programs have grown only more sophisticated. While additional sanctions will hurt, North Korea has long been economically insulated by its relationship with China, its northern neighbor and main trade partner, which fears that strict sanctions could undermine the Pyongyang government, unleashing chaos.

While North Korea’s economic isolation and the international financial system make it tricky to identify sanction targets and prove violations, the new U.S. legislation could hit companies in China that deal with the North, including those that buy its main exports — coal and minerals.

Lately, even Beijing has appeared more willing to support economic punishment for Pyongyang. In part, that reflects Chinese nervousness about discussions between Washington and Seoul over the deployment in South Korea of a THAAD missile network, one of the world’s most advanced missile defense systems.

On Monday, the Chinese government-run English-language China Daily called THAAD a serious regional security threat, and said that “a sanctions package that is sufficient for Pyongyang to reevaluate its nuclear program,” would stop its deployment.

“For that to happen,” it said, “the new U.N. resolution must truly bite.”

DIPLOMACY

Is North Korea a nuclear state? That question has largely paralyzed major diplomatic efforts on the Korean Peninsula for years.

The main diplomatic forum to try to get Pyongyang to abandon its nuclear program, the so-called six-party talks, hasn’t met since 2008. Washington insists that Pyongyang show it’s willing to end its nuclear program for the talks to begin again. Pyongyang, meanwhile, insists it is now a full-fledged nuclear power and demands that the world — and especially Washington — treat it as such.

Washington did engage directly with the North in 2012, but a painstakingly negotiated food-for-nuclear-disarmament deal fell apart weeks later when the North staged a rocket launch that Washington says was a banned missile test. That hardened the positions of many North Korea specialists in Washington.

Some in the international community now believe that North Korea will never abandon its nuclear program, and say the only way to negotiate with the North is to accept it as a nuclear power and work on a freeze, and then gradual arms reductions.

But with Washington steadfastly refusing to accept North Korea as a nuclear state — and North Korea steadfastly insisting it is one — diplomacy remains frozen.

MILITARY RESPONSE

What about simply erasing North Korea’s weapons programs, launching missiles to destroy its weapons facilities? That strategy worked for Israel, some argue, when it sent bombers to destroy Iraq’s Osirak nuclear reactor in 1981.

Since the 1950s, though, the South Korea and the United States have wrestled — both internally and sometimes with each other — over how to respond to North Korean aggressions, from the 1968 guerrilla attack on South Korea’s presidential palace to the 2010 shelling of the South Korean island of Yeonpyeong.

Again and again, though, the decision has been made to avoid military action. The immense danger on the Korean Peninsula is that any military response from the South could quickly spiral into all-out war. And with nearly half of South Korea’s 50 million people living in or around Seoul — just 50 kilometers (35 miles) from the border and within range of the North’s artillery batteries __ Pyongyang could inflict immense damage on its rival in just minutes.

The potential risks are simply too high.

Can South Korea and the United States “bear the risks of suffering casualties on our side too?” asked Lim Eul Chul, a North Korea expert at South Korea’s Kyungnam University. “I don’t think the U.S. and South Korean leaders can afford that.”

KAESONG

Just days ago, Seoul ordered the closure of the jointly run Kaesong industrial park, a manufacturing complex just inside North Korea, saying Pyongyang had funneled most of the money from the park into its weapons programs.

Shutting the park will be painful for Pyongyang, but it will not cripple it. North Korea is a deeply impoverished country, with little industry and, because of sanctions, little trade with any nation but China.

Kaesong, where more than 120 South Korean companies employed more than 54,000 North Koreans, was an easy source of income for the North. Instead of paying the workers directly, money went to the North Korean government — $120 million last year alone — which then paid only a fraction of that to the workers, South Korea says.

North Korean exports to China, though, are estimated to be 20 times higher than what it earned from industrial park. So unless China goes along with significant new sanctions, North Korea will be able to absorb Kaesong’s closure and keep its economy hobbling along.

___

Associated Press writers Hyung-jin Kim and Foster Klug in Seoul and Matthew Pennington in Washington contributed to this report.

![일본 사도광산 [서경덕 교수 제공. 재판매 및 DB 금지]](http://www.koreatimesus.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/PYH2024072610800050400_P4-copy-120x134.jpg)