- California Assembly OKs highest minimum wage in nation

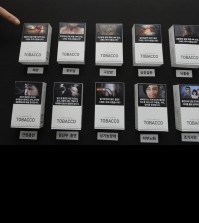

- S. Korea unveils first graphic cigarette warnings

- US joins with South Korea, Japan in bid to deter North Korea

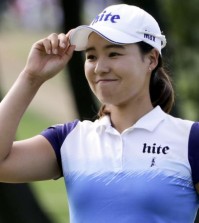

- LPGA golfer Chun In-gee finally back in action

- S. Korea won’t be top seed in final World Cup qualification round

- US men’s soccer misses 2nd straight Olympics

- US back on track in qualifying with 4-0 win over Guatemala

- High-intensity workout injuries spawn cottage industry

- CDC expands range of Zika mosquitoes into parts of Northeast

- Who knew? ‘The Walking Dead’ is helping families connect

Ill Californians may take life-ending drugs starting in June

FILE — Debbie Ziegler, mother of Brittany Maynard, speaks to the media after the passage of legislation, which would allow terminally ill patients to legally end their lives, at the state Capitol, Friday, Sept. 11, 2015, in Sacramento, Calif. The measure to allow doctors to prescribe life-ending medication succeeded on its second attempt after the heavily publicized case of Maynard, the woman with brain cancer who moved to Oregon to legally take her life. (AP Photo/Carl Costas)

SACRAMENTO, Calif. (AP) — Terminally ill California residents will be able to legally end their lives with medication prescribed by a doctor starting this summer, ending months of uncertainty for dying patients hoping to turn to the practice.

State lawmakers adjourned a special session on health care Thursday, paving the way for the law allowing physician-assisted suicide to take effect June 9.

The law approved last year made California the fifth state in the nation to adopt the practice, but patients were left in limbo until the special session wrapped up and the law could take effect 90 days later.

It passed following the heavily publicized case of Brittany Maynard, a 29-year-old California woman with brain cancer who moved to Oregon to legally end her life in 2014.

Supporters say they do not know how many terminally ill patients have been waiting for the law to go into effect. Opponents say it could lead to premature suicides.

One prominent advocate, Christy O’Donnell, a 47-year-old single mother with lung cancer who sued the state to demand the right to life-ending medication, died last month at her home north of Los Angeles before getting the option.

Elizabeth Wallner, a Sacramento resident with stage 4 colon cancer that has spread to her liver and lungs, said she is relieved a date has been finally set.

“It gives me a great peace of mind to know that I will not be forced to die slowly and painfully,” Wallner said in a statement provided by Compassion & Choices, a right-to-die advocacy group that worked closely with her and others to campaign for the law.

Marilyn Golden, a senior policy analyst with the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund, said the law doesn’t go far enough to protect people from being coerced into a premature suicide by an abusive caregiver or heir. It also could allow people denied medication by one doctor to shop around for the lethal drugs.

The California Catholic Conference, which opposed the law, said it would increase support for the dying.

“Quality palliative case, spiritual and emotional support and a respect for our human dignity are the compassionate response — not a lethal dose of drugs from a physician,” Executive Director Edward “Ned” Dolejsi said in a statement.

Democratic Sen. Bill Monning, who helped author the bill, said patients or their family members have been contacting his office daily since Gov. Jerry Brown signed the legislation last October.

“It’s obviously a great sense of achievement and historic achievement for California, but it is tempered by the loss of great people who fought to get the billed passed,” he said.

California’s law includes strong protections for both patients and physicians, Monning said.

Religious institutions, like Catholic hospitals, can opt out and ban their doctors from participating in any assisted deaths. Patients must have two separate meetings with a physician before a doctor can prescribe a life-ending drug.

If there is any doubt over the person’s mental capacities, physicians are required by law to refer the patient to a mental health care provider. Certified translators must also be required for patients who are non-native English speakers.

Bradley Williams

March 12, 2016 at 11:00 AM

Your source has done you a disservice. The promoters of assisted suicide have worn out their thesaurus attempting to imply that it is legal in Montana. Assisted suicide is a homicide in Montana. Our MT Supreme Court ruled that if a doctor is charged with a homicide they might have a potential defense based on consent. The Court did not address civil liabilities and they vacated the lower court’s claim that it was a constitutional right. Unlike Oregon no one in Montana has immunity from civil or criminal prosecution and investigations are not prohibited like Oregon. Does that sound legal to you?

Perhaps the promotors are frustrated that even though they were the largest lobbying spender in Montana their Oregon model legalizing assisted suicide bills have been rejected in Montana in 2011, 2013 and 2015. They got nothing for their investment to buy a license to sift through our seniors for their wind fall profit.