- California Assembly OKs highest minimum wage in nation

- S. Korea unveils first graphic cigarette warnings

- US joins with South Korea, Japan in bid to deter North Korea

- LPGA golfer Chun In-gee finally back in action

- S. Korea won’t be top seed in final World Cup qualification round

- US men’s soccer misses 2nd straight Olympics

- US back on track in qualifying with 4-0 win over Guatemala

- High-intensity workout injuries spawn cottage industry

- CDC expands range of Zika mosquitoes into parts of Northeast

- Who knew? ‘The Walking Dead’ is helping families connect

Korea’s ‘webtoon’ industry: boom or bust?

Cartoonists continue to struggle, despite online readership boost

By Baek Byung-yeul

Koreans love cartoons as long as they don’t have to pay for them.

Free online comic strips, or “webtoons,” are the reason many commuters keep their eyes glued to smartphones on buses and subways. It’s a safe assumption that more people are reading cartoons than ever.

But despite the increased readership, the majority of Korean cartoonists continue to struggle simply because not enough people are buying their comic books.

It would be inaccurate to blame webtoons for the decline of traditional, paid content.

A truer assessment would be that the market for Korean comics never really recovered from the overweening government suppression during the 1990s when cartoons were demonized as harmful influences to young people, displaying paternalism at its worst.

School children were discouraged from buying comic books, punished for simply carrying them in their bags. A slew of publishers suffered and fell, killing the creative vibrancy of the scene and affecting a wider generation of readers who moved on to other cultural mediums.

While high-speed wireless networks and mobile Internet devices gave cartoons a second life, most cartoonists agree that things were better in the old days.

For cartoonists, the Internet doubles as an opportunity and threat.

Cartoonist Huh Young-man is busy at work in his studio in Seoul in this Nov, 2007 photo. Huh represents the older generation of Korean cartoonists

who used to thrive in print publishing. (Korea Times file)

Webtoons are an effective platform for young artists to establish their works and develop an audience thanks to their low entry barriers and strength as a media.

But the sea of free content is also reinstating consumers’ reluctance to spend money on comics and artists have struggled to find a reliable model to monetize their content online.

To Internet companies such as Naver (www.naver.com) and Daum (www.daum.net), cartoonists are merely one of their many tools to drive traffic. While these companies will compete to get high-profile cartoonists to post on their sites, the majority of artists are poorly compensated if at all. It’s fair to say that the business model of webtoons is based on exploiting their desperation for exposure.

“Unlike Japanese ‘manga,’ which continues to drive a large part of the country’s publishing market and provide a creative influence to movies, music and video games, Korea’s cartoon culture was deprived of its opportunity to thrive,” said Lee Chung-ho, cartoonist and president of the Korea Cartoonist Association (KCA), which represents more than 1,300 artists.

“However, the most difficult process for us will be to find a sustainable business model. Readership has increased dramatically through webtoons, but you have no clear idea on how many of these readers will be willing to pay for content.”

Burn, burn, burn

Kim Hyung-sik, a 37-year-old office worker, is a hardcore cartoon enthusiast with an impressively large collection of comic books taking up a wall in his room. He says it wasn’t always easy to maintain his passion for cartoons.

“Whenever my parents saw me reading cartoons when I was a kid, they went ballistic,” he said.

“They ripped my books. They would hit and spank me and I would go to school with my legs bruised. This was an experience I shared with many of my classmates.”

Kim’s story is a common one in a country where schools used to pick a day in May to gather the many comic books impounded from students and burn them in the schoolyard, one of the strangest rituals honoring the month designated by the state as “month of the family.”

The book burnings, which were encouraged by government officials, continued until the late 1990s. The biggest of these ceremonies was held every year in front of the Seoul City Hall, where municipal authorities invited the national media to record the spectacle of thousands of comic books going up in flames.

Cartoons were demonized then for the same reasons politicians are demonizing video games now.

They were blamed for encouraging a culture of violence and sex. The truth is that politicians, lawmakers and teachers were merely catering to Korea’s famously overzealous parents, who want their kids to do nothing but download English words to their brains 24/7.

Things took an irrevocable turn for the worse in 1997 when the culture ministry named cartoons, along with cigarettes and alcoholic beverages, as “harmful substances” for youngsters.

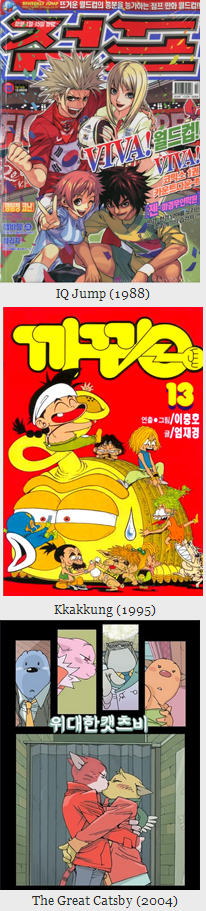

Cartoon magazines, which had thrived in the 1980s and earlier part of the 1990s, were doomed because storeowners were restricted from selling them to their main audience.

“The heyday of Korean cartoons was short. Censorship was heavy during the military governments. In the 1980s and early 90s, there were a few authors who were selling copies in the several millions. Huh Young-man’s works were popular and the Japanese series, ‘Dragon Ball’ by Akira Toriyama, was probably the most popular comic series ever,” said Lee of KCA.

“The government suppression of the 1990s was a decisive blow. Policymakers loosened their grip simply because cartoons had lost much of their relevance as cultural products. But the readership of cartoons recovered in the 2000s when they were offered as free Internet content.”

History will always attempt to repeat itself.

Seventeen years after policymakers put cartoons in the same category as tobacco, lawmakers of President Park Geun-hye’s party are pushing a controversial law that groups video games with booze, drugs and gambling as the country’s “four major” addictive substances to be put under tighter control. For reasons only they could comprehend, cigarettes were left off that list.

Webtoons go mainstream

Huh represents the older generation of Korean cartoonists who used to thrive in print publishing. Kang Do-ha, Kang Full and Yoon Tae-ho highlight the new generation of cartoonists who managed to establish themselves on the Internet.

According to a study by the KT Economic Research Institute, the country’s market for online cartoons will be worth around 210 billion won ($195 million) at the end of this year, compared to 100 billion won in 2012.

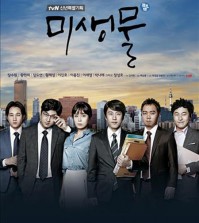

The researchers said they based their calculation on the increased sales in online advertisements and intellectual property income, which is increasing dramatically as webtoons grow as a source of creative input in movies, television dramas and video games.

“Webtoons are entering their golden age thanks to the explosion in mobile phones,” said researcher Kim Jae-pil, one of the authors of the KT study.

“There is enormous room for exports as digital formats represent only 10 percent of the worldwide cartoon market now and Korea is much more advanced in this field than other nations.”

It could be debated whether KT’s numbers are inflated or not, but there is no argument that that webtoons represent a rapidly expanding market.

However, the long-term future will depend on whether artists and online publishers can find a way to distribute the fruits of the growth more broadly, which is tricky because consumers aren’t directly paying for the content.

It was in September last year when several cartoonists staged a protest against Kiwitoon, an online carton publisher, over what they claimed as unfair contracts. In exchange for providing lesser-known artists a platform to publish, Kiwitoon required them to give up their share in copyright, advertisement revenue and also prevented them from publishing different cartoons in other platforms.

Kiwitoon improved the contract conditions only after KCA threatened a full-blown boycott of its website.

“A lot of online webtoon publishers have been operating like Kiwitoon,” Lee said.

“This is why the KCA is devoted to a ‘clean contract’ campaign to strengthen the rights of the artists and ensure they get a fairer share of what their products are generating commercially.

“Previously, our membership was limited to cartoonists who have released their work in print, but we are now also allowing artists who have only published online to join us.”

Lee is one of the few cartoonists who experienced dual success in the magazine era and webtoon era. His romantic comedies “My Love” and “Kkakkung” were among the popular comic series of the early 1990s when they were published in the weekly IQ Jump.

His “Murim Investigation Team,” an adventure series revolving around private detectives with different martial arts skills, has been one of the most popular webtoons on Daum since it was first published in 2007.

In addition to campaigning for fair contracts, Lee also plans to establish “manhwa academy” in order to provide reeducating program for the older generation of cartoonists, who are struggling to adapt to the online format.